The 1969 Woodstock music festival, which featured performances by artists like Joni Mitchell, Jimi Hendrix, and The Who, seared its way into the public consciousness almost immediately and became an almost mythical touchstone for the anti-establishment movement of the 1960s.

But that same summer, 100 miles away, the Harlem Cultural Festival – which would later be nicknamed “Black Woodstock” – featured an equally incredible lineup of Black musicians and performers. Even though it was filmed by a professional crew, the footage was never picked up by a film distributor or broadcast network, so it sat in a basement for 50 years. Thankfully, though, Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson of The Roots has exhumed it and used this amazing archive as the backbone of his feature directorial debut, a documentary called Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised).

Spread over six consecutive weekends in the summer of ’69 and drawing a total crowd of around 300,000 people, the Harlem Cultural Festival featured an unreal lineup: Nina Simone, Sly and the Family Stone, B.B. King, Stevie Wonder, Gladys Knight and the Pips, The 5th Dimension, and many, many more, who command the stage in Harlem’s Mount Morris Park. Questlove feels like an archaeologist who has unearthed an ancient treasure, unveiling stellar performances of classic songs like “Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In,” “Everyday People,” “Oh Happy Day,” and “My Girl,” and interspersing them with current interviews with several of the surviving artists, a handful of attendees, and even the people who filmed the show.

I imagine it may have been tempting to simply present this footage in the form of a pure concert film. But while the first-time director absolutely allows the audience to revel in the music, the atmosphere, and the uninhibited Blackness of this forgotten festival, he also uses it as an opportunity to recount the history of Harlem during that era, using certain songs and musical acts as jumping-off points to explore the social and political changes that they represented (or, in some cases, helped inspire).

It tackles the intersection of musical styles and society, touching on how gospel music provided a means of cathartic expression for people who were feeling stifled, and how Sly and the Family Stone’s more psychedelic soul style and gender parity on stage was a turning point for Black music. “The goal of the festival may very well have been to keep Black folks from burning the city in ’69,” someone says, and the film sketches in details about the high-profile political assassinations that occurred across the ’60s. That segment of the doc culminates with Reverend Jesse Jackson recounting Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination on stage, which leads into an extended, hyper-soulful performance of his favorite song, “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” performed by Mavis Staples and “The Queen of Gospel” Mahalia Jackson.

And while Black artists, music, and styles are the primary focus here, the footage also reflects Harlem’s cultural melting pot through its inclusion of Puerto Rican, Dominican, and Jamaican performers and audiences, and Questlove uses that as an opportunity to address how those cultures’ musical influences helped tie Harlem together. (Lin-Manuel Miranda and his father Luis are even talking heads at one point.) The movie drags a little at times during history lessons like these, and not nearly enough time is spent on the producer who filmed these concerts and why the ended up in his basement for five decades, but overall, the electricity of the music and the novelty of seeing some of these performers absolutely shred during this period of their careers easily overshadows any of its flaws.

In ESPN’s Michael Jordan documentary series The Last Dance, filmmaker Jason Hehir handed his interview subjects iPads and showed them clips to generate reactions, which turned out to be a terrific decision that led to some of the show’s most memorable (and meme-able) moments. Questlove does something similar in Summer of Soul, showing his interview subjects clips from this long-buried footage on a big screen while the cameras roll. But instead of quips and oversized reactions like in The Last Dance, the subjects here shed tears – not just because of the sheer power and brilliance of the music, but because a record of it exists. In addition to being a celebration of this specific historic event, Summer of Soul makes a powerful case for the act of preservation in a larger sense, and shows in stark terms how documenting and maintaining something can be an invaluable affirmation of not only cultural history, but individual identities.

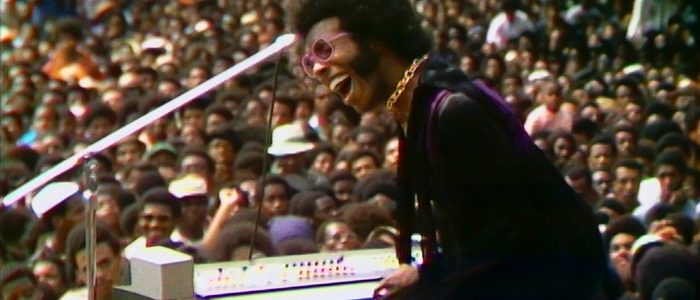

In many ways, this is a film about priorities – whether it’s the need to preserve the stories of marginalized communities, or more literally commenting on this country’s prioritization of reaching the moon instead of providing much-needed aid to communities of color. But it’s also an unrestricted glorification of Black pride expressed through a universal language. For all of the film’s contextualizing, the lasting impact of the Harlem Cultural Festival may best be summed up in the image of a stylish, 19-year-old Stevie Wonder playing his heart out on the keyboard and getting swept up in his own song as tens of thousands of smiling people looked on in awe. Bearing witness to something, the film seems to say, can sometimes be almost as important as the thing itself.

/Film Rating: 8.5 out of 10

The post ‘Summer of Soul’ Review: A Joyous Celebration of a Forgotten Music Festival [Sundance 2021] appeared first on /Film.

from /Film https://ift.tt/2L27Pa7

via IFTTT

Comments

Post a Comment