Fandom is a religion that thrives on killing its own gods. In Neon Genesis Evangelion, there’s a passing line of dialogue that suggests self-destruction is the natural endpoint of evolution. The Japanese television and film series periodically evokes deicide with exotic Judeo-Christian imagery, such as god-killing spears and figures nailed to crosses. Yet it’s known for the line, “The fate of the destruction is the joy of rebirth.” Evangelion is a franchise that evolved to the point of self-destruction, only to be reborn, or rebuilt, numerous times over. Its latest rebirth is on Netflix, where it became available to watch last Friday.

The ability to conveniently view one of the greatest anime works of all time should be cause for celebration among U.S. fans, whose main avenue for watching the series since the DVDs went out of print years ago has been illegal streams, expensive copies from third-party Amazon sellers, or the sketchy online market of bootlegs. Due to licensing entanglements, however, the situation with Evangelion has come to resemble Star Wars, whereby the original, unaltered theatrical trilogy is unavailable on home media. Here again, the version that is out there for mass consumption is different from the one fans first experienced, with redubbed voices, new subtitles, censored relationships, and missing music.

The reaction on social media had been typically harsh, enough so that it almost plays right into Evangelion’s metaphorical god-killing cycle, as complaints drown out discussion of the anime epic’s lasting virtues and the baby gets thrown out with the bathwater all over again. What’s important is that the series is catching a wave of renewed interest, and as it finds a fresh audience, it’s ripe for discussion, particularly as it relates to themes of personal dysfunction, social withdrawal, and the intersection between fan culture and storytelling.

This article contains spoilers for the entire series.

The Evangelion Bible: New Revised Netflix Version

In Neon Genesis Evangelion, the fate of the world rests on the shoulders of a lanky mech piloted by a 14-year-old. If Shinji Ikari could just manage to get his act together, he might actually be a hero. As it is, he’s a self-loathing mess who is often depicted hanging his head in shame and who is likely to strike some new viewers (or even old ones) as a pathetic protagonist. But really, that’s the whole point.

Creator Hideaki Anno’s struggle with depression deeply informs the character of Shinji, just as end-of-the-world fears fuel Evangelion, an easily binge-able, 23-minute show that began its run on Japanese television in 1995, months after a devastating earthquake struck the city of Kobe and a doomsday cult carried out the Tokyo subway sarin attack. As a resident of Tokyo, I may have a slightly different perspective on the Netflix iteration of Evangelion, especially since my day job is that of a language teacher, meaning that much of my existence revolves around the fluidity of words and their meanings. In general, I think that once a thing ceases to be fluid and starts to become rigid, it’s as good as dead.

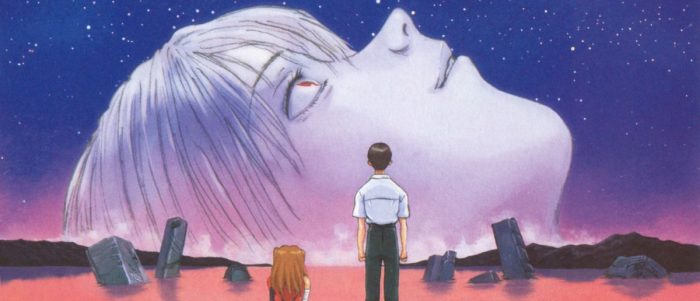

Years ago, before leaving the states, I divested myself of all DVDs, abandoning physical media for digital purchases via the iTunes Store. This included my eight-disc Neon Genesis Evangelion: Perfect Collection set, as well as my copies of the two movies, Death and Rebirth and The End of Evangelion. In college, those movies, along with the 1988 classic Akira, were my introduction to anime. The End of Evangelion, in particular, left me thunderstruck with its apocalyptic imagery, and to this day, it remains my favorite anime film.

I always just sort of took it for granted that if wanted to, I could go out and buy Evangelion on Blu-ray at a store in Tokyo. Not everyone has this Blu-ray option at their disposal, and I can appreciate how frustrating that might be. This week, I mounted my Evangelion rewatch on Netflix Japan, where the integral outro song, “Fly Me to the Moon,” was intact at the end of every episode. As a fan of “Ewok Celebration” (a.k.a., “Yub Nub,” the original song at the end of Return of the Jedi, before it received the Special Edition treatment), I can appreciate, also, how stateside Evangelion fans would decry the loss of “Fly Me to the Moon.”

With the Netflix translation of Evangelion, there’s been a lot of hand-wringing about the changing of certain lines of dialogue, too. That didn’t bother me any more than it would if I was at the bookstore and saw a new translation of a classic work of literature like Dante’s Inferno (which, in the Rebuild of Evangelion film series, helps furnish the levels of Nerv’s Bethany Base with names, so that they sound like the Circles of Hell.)

Again, I can understand the disgruntlement about seemingly unnecessary changes. Texts like Evangelion become as sacred as a bible to some fans, which is fine until you stop to think that the actual, you know, Bible-bible has been translated and re-translated, interpreted and re-interpreted, ad nauseam. Which is the “correct” translation (if there even is such a thing): the King James Version, the New Revised Standard Version, or one of the other innumerable versions? The way I look at it, only a literalist or fundamentalist would get so caught up on the details in a book of parables that he or she missed the point of the parables entirely.

Evangelion is a parable about a dysfunctional human being and his fumbling attempts at being a participant in life, which eventually lead to a burgeoning selfhood on his part. Shinji Ikari was born to pilot an Eva … he just doesn’t know it right away. No sooner does he arrive at Nerv Headquarters in the first couple episodes than he’s having to leap into the fray with zero experience.

At that point, he can barely walk in his Eva. We’re initially led to believe that his first at-bat proved disastrous, as it cuts from the Angel pummeling his Eva on the battlefield to him waking up under the “unfamiliar ceiling” of a bleached-out hospital room.

The twist comes when there’s a flashback later, revealing that he won the battle and is a something of natural when it comes to Eva piloting: able to tear through glowing force fields, or A.T. Fields, and dismantle his Angel opponent. If only that could cure loneliness…

Shinji Ikari, God’s Lonely Man

Shinji craves approval and when he doesn’t get enough of it, his efforts leave him hollowed out, going through the motions of shooting a gun while robotically repeating the words, “Center the target, pull the trigger.” In his new bunking place at Misato’s apartment, he lays on his bed, replaying moments from the day’s interactions in his head. He can’t even bring himself to unpack the boxes in his room. He spends much of the time with his ears walled off by headphones, listening to music, playing and replaying tracks 25 and 26 on his Walkman, as if Anno already somehow knew that he would one day cycle back on those same episode numbers with Evangelion.

Shinji runs away from Nerv, attempting to quit, only to return and face the same hedgehog’s dilemma whereby the closer he gets to people, the more he gets hurt. Quiet at dinner parties, he just doesn’t know how to act around people, we’re told. He has a growing network of acquaintances but he’s “the sort of person who can’t make friends easily.” At school, he gets punched around by his own Flash Thompson, Suzuhara, who goes from bullying him to being his most vocal cheerleader and eventually his unwitting victim in an Eva-on-Eva fight.

Like his aloof father and his fellow pilot, Rei, Shinji is simply “all thumbs at living.” He undergoes “unison training” with Asuka, but he’s perpetually out of synch with her and the world around him. The one constant is that he endeavors to please his father and people in general, yet as his new friend (maybe, first real friend) Kaworu notes toward the end of the series, he goes to extremes to avoid making first contact with anyone. If he avoids other people, he’ll never be betrayed.

Not realizing that “people can’t handpick a series of pleasant events to make up their lives,” Shinji has (again, we’re told) spent his whole life ignoring or avoiding anything he doesn’t like. In this respect, he’s maybe cut from the same cloth as the rest of the Tokyo-3 populace. Fuyutsuki, who serves as a second-in-command to Shinji’s father, describes the city as “a paradise we built for ourselves to insulate our kind from the terror of death and satisfy our carnal desires” It’s a city of cowards, he says, “shelter for those fleeing an outside world full of enemies.”

As the series progresses and Shinji’s confidence as a pilot takes shape, being inside the Eva, taking up the fight against the Angels — wrestling with these gods — is how he comes to justify his existence. It’s not so different from the life of an otaku, Japanese, American, or otherwise, who seeks fulfillment in his or her own fandom, saddling up street-side in a lawn chair to cheer and heckle the procession of pop culture giants, year after year. Maybe Shinji’s there along the parade route, too: “just sitting around, waiting for someone to bring false happiness to him.”

Shinji’s not the only one who lives to impress the father who abandoned him. When Misato talks about her father, she describes him as, “A man who lived in his own dreams. A man who was absorbed in his research. A spineless man who couldn’t stomach reality.” Then she realizes that she and her father are just like Shinji and his father.

Gendo Ikari never paid any attention to his family, either. It left his motherless child struggling to fill the hole in his heart where a parent’s love should have been. Asuka pointedly teases Shinji about this, asking him if being in the entry plug of his Eva feels like being back in the womb. On the outside, an umbilical cable connects his unit with a power source, while on the inside, said entry plug is filled with LCL, a breathable liquid that surrounds Shinji like amniotic fluid.

Fans are weaned on a steady diet of pop culture; Shinji is weaned on a succession of Angel battles. One of those battles ends with his Eva going berserk and eating the Angel it has defeated. Shinji has already learned to miraculously reactivate the Eva unit after it has detached from its umbilical cable and its 5-minute power supply has run down … but when it devours the Angel, it also absorbs the Angel’s engine, giving it a new source of unlimited energy. For the first time, it and its young pilot stand truly self-sufficient.

Continue Reading Evangelion >>

The post ‘Neon Genesis Evangelion’ and the New Religion of 21st-Century Fandom appeared first on /Film.

from /Film http://bit.ly/2J4pVmU

via IFTTT

Comments

Post a Comment