‘Screwball’ Filmmakers Explain Why They Used Child Actors in Their Hilarious True-Crime Doc [Interview]

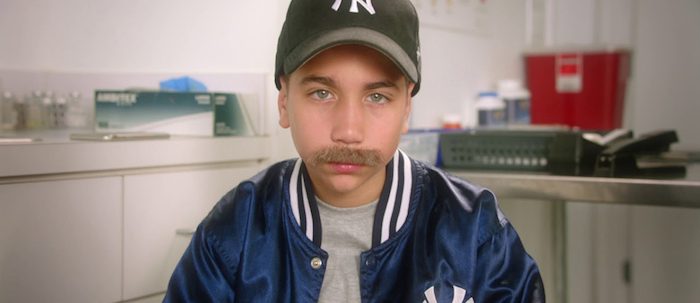

Screwball is a true-crime story documentary about the Biogenesis scandal that shook Major League Baseball to its core. But there’s one unique twist: child actors are used in all of the re-enactments, transforming the whole story into a deranged comedy. Miami-based filmmakers Billy Corben and Alfred Spellman are Florida-centric in their filmography, so it would not surprise me in the slightest if they do a documentary on the Marlins Park at some point in the future.

I sat down with director Billy Corben and producer Alfred Spellman during the 2018 Toronto International Film Festival to chat about their funny and surprising new doc. Screwball opens in limited release on March 29, 2019.

Congrats on the world premiere.

Alfred Spellman: Thank you.

Billy Corben: Thanks.

Can you talk about how much of an honor it is to have the film premiere in Toronto?

Billy Corben: It’s tremendous. We’ve never been here. I’ve been to Toronto before but never invited to the Toronto International Film Festival. And I got to tell you it was—I was anxious. It was a little nerve-racking. I guess my perception from afar of the festival is it’s such a star-driven event. There’s such big movies here. A lot of competition. I wondered if anyone would come to see our little documentary you know. And it’s a testament to the audiences and to the passion for filmmaking and nonfiction filmmaking that they would show up to a documentary like ours when we’re competing with Julia Roberts and Hugh Jackman and Chris Pine and every other major star of the universe and a galaxy is here. It was incredible and really heartening to see a sell-out last night (September 7th) and I would easily say in a 20-plus year career one of if not the best audience that we’ve ever had. It’s really encouraging when you’re in your bubble for almost a couple of years creating something and you hope that it turns out the way that you want it to—you hope that people will get it in the manner in which it’s intended and hear that audience laugh. We hoped they would gasp when we hoped they would heckle when we hoped they would. It was it was really in a now over two decade career, it’s one of the most fun experiences I’ve ever had watching one of our movies.

Now as the Biogenesis scandal unfolded, when did you realize that this could be the basis of a documentary?

Billy Corben: Right away. I think I mean—being native Floridians and being students of Florida fuckery, steeped in it, raised in it, baptized in it, I think that we’re always on the lookout for compelling characters and stories. And this had been on our list for the moment the story broke.

Alfred Spellman: You can’t imagine Carl Hiaasen or Elmore Leonard writing this story as crazy as this—a four thousand dollar loan that went bad, these tanning salons, and fake doctors offices in South Florida. It was almost custom-made for us.

Billy Corben: Leading to the end of the career of the highest paid baseball player in history. I mean it’s just you know where nothing makes sense. The facts don’t make sense. The motivations don’t make sense. The fallout does it doesn’t make any sense. It was just like it was something that we had hoped that someday we would get a chance to tell but not but you can never be sure.

Rather than go to basic documentary route you went for that true crime story but one that plays to that comedy angle with these child actors. How did you come up with that decision?

Billy Corben: Well the germ of the idea—the seed of the idea is is over 20 years old. It was Spike Jones is B.I.G. video from 1997, “The Sky’s The Limit,” where he used child actors to do a straight faced or otherwise straight faced Bad Boys record-style music video because it was done posthumously. And so he hired a baby Biggie and a baby Puffy and a baby Lil Kim and a baby Busta Rhymes and came up with a creative solution to a challenge and we had a similar challenge here where what were we going to do for B-roll. This was not a sports documentary so we couldn’t just use a bunch of baseball footage in it so that was not a solution. We knew we were going to have to do re-creations and we knew coming into this that what our perspective was. It was always called Screwball. So the idea was always have a take a tongue on cheek approach to this. And so you know when I was listening to the interviews, it struck me how much the adults acted like children. And also luckily, the storytelling styles of Porter Fischer and Tony Bosch—our primary subjects and mortal enemies—had very comparable styles of storytelling where you went on a journey with them. You were flashing back to in-the-moment recounting of an episode, of an event, and they would do dialogue. He said this to me, and then I said this back, and then he yelled at me and then he—It was so descriptive I was like oh, shit, this is our dialogue. We’ve just got to Drunk History-style it with playback on-set actors lip synching the actual interview audio. The only difference is the actors are 8, 9, 10 years old.

The world premiere, if I recall correctly, was 20 years to the day that Mark McGwire hit his 61st home run.

Billy Corben: Holy shit! You’re the first person to bring it up. We were just talking about that.

Alfred Spellman: September 8, 1998 (note: the interview took place on the 8th, the 20th anniversary of McGwire’s 62nd home run). After the baseball strike, Major League Baseball needed fans to come back to the game so the McGwire-Sosa home run chase and Cal Ripken’s consecutive game streak in 1995. Those two events from the 90s really reignited the country’s interest and passion in baseball, and ultimately led us to the Biogenesis story.

Billy Corben: And I think it’s appropriate in 2018 with the state of the United States and the state of the world that we celebrate this anniversary of cheating to get ahead—cheating to get ahead! (Laughs)

Alfred Spellman: It feels a very 2018 story to tell.

That’s one of those anniversaries that I didn’t even think about a few weeks ago like I was so focused on The Big Lebowski, Deep Impact, Armageddon. I’ve been so movie-focused. I mean I’m sitting next to another film critic during Boy Erased—a fellow St. Louis Cardinals fan. There’s a few of us here.

Alfred Spellman: You’re from Chicago and you’re a Cardinals fan?

I grew up in Louisville. We the AAA affiliate.

Alfred Spellman: The Louisville Redbirds, right?

Yeah. Until 1998, when they ditched us from Memphis.

Alfred Spellman: That’s right. Yeah I was going to say that must get you in some trouble some time in Chicago.

The Cubs won the World Series the same day we put our dog down.

Alfred Spellman: Ah, geeze.

I was not home for that so it was very depressing. It’s easy living a half mile from Wrigley.

Alfred Spellman: I’m sure.

Billy Corben: I’d apologize to Montreal but Jeff Loria got us pretty good, too, down in Miami with the Marlins.

Just sells off the team multiple times—wins the World Series—goodbye!

Billy Corben: And we said we made that multimillionaire a billionaire with our tax dollars building that stadium. Classic Miami hustle. Another one.

Could that be another documentary?

Billy Corben: Oh, fuck, yes! Big fucking yes!

Alfred Spellman: Screwball is actually—we’ve kind of envisioned it as the backdoor pilot for a series that we’ve always wanted to do. Billy and I often say that we wish we had like a 60 Minutes or a Dateline-type of format and we could tell 18 or 20 minute stories because there so many of that don’t deserve the full feature film.

Billy Corben: The Florida fuckery series.

Alfred Spellman: So we have a series called The Sunny Place for Shady People that will hopefully follow on and the Marlins stadium fiasco is right up there on the a list for stories to tell.

Billy Corben: High on that list.

Hopefully, the current owner treats them so much better. It’s a disservice.

Alfred Spellman: The current ownership in the British Virgin Islands?

Isn’t Jeter a part of the current ownership?

Alfred Spellman: He is and they have basically decided that as part of the stadium deal, the Marlins were supposed to pay the taxpayers a percentage of the deal if they sold for a certain price. Of course there was no profits to be had apparently and when the people took the Marlins to court, they said, “You can’t take us to court here because we’re a British Virgin Islands company.”

Billy Corben: Which was news to me. Why didn’t they pay for the fucking stadium instead of us is what I want to know. If they’re the BVI Marlins and not the Miami Marlins, or let them fucking pay for this three point five billion dollar three point two billion with a B dollars ballpark for crying out loud. Can you tell we’re bitter about it?

Yeah, I would be, too.

Billy Corben: Yeah. It’s sad that our great-great-great grandchildren are going to be paying for this to make Jeff Loria a billionaire. That a great thing—I would say that Los Angeles is where you go when you want to be somebody. New York is where you go when you are somebody. Miami is where you go when you want to be somebody else. So we knew who Jeff Loria was when he came in the door based on Montreal and yet we still gave them the key to the city and county’s treasury.

Going back to steroids and on the baseball subject do you feel that MLB did not do enough during the 90s and early 2000s to get it out of the game and do these guys belong in the Hall of Fame?

Alfred Spellman: Well, I would say two things about that. Number one, I think that we need to have an honest discussion about performance-enhancing drugs. I always use as an example Mickey Mantle Billy Martin out all night the Copa Cabana in the 50s and 60s getting drunk and trying to play a 1 PM day game at the Yankee Stadium. Everybody was taking amphetamines. And there was the testimony during the 1980s drug trials that Willie Mays had the red juice in his locker. You know so now that we’re now post-anabolic steroids—now we’re talking HGH and testosterone. So it’s a wack-a-mole game. At some point, we have to decide what exactly is a performance-enhancing drug. If I take a Tylenol to reduce my muscle inflammation, is that a performance enhancer? Or coffee to wake up for a game the next day? In the old days, caffeine would be a performance-enhancing drug, too, I suppose. Certainly, there’s a different scale but ultimately at the end of the day you have to decide what we’re going to call these things. Nowadays, we have 10 percent of baseball players with Adderall prescriptions because I guess they all have ADHD but the more likely it’s to be able to get through a 162 game season in 181 days and that’s a grueling schedule. And so, did baseball do enough? No, obviously not. But the question is—you have union concerns, obviously. You have very strong players association and move and Marvin Miller would have made the argument that these guys are Americans—they have a fifth amendment right against self-incrimination and unless there’s a reasonable suspicion how could you have mass drug testing like these. These guys aren’t in a public safety job like an airline pilot or a government employee or even a police officer, which we don’t even test for the most part for steroids. So you know what is the hysteria that surrounds performance-enhancing drugs in baseball—is it justified?

Billy Corben: I would argue know steroids in baseball is not a thing worth making a federal case out of but that’s exactly what they did. Congress exercised its oversight authority over this over this monopoly that they had granted an antitrust exemption to. So be it, it is their authority. But I would say if Congress is going to have oversight against anyone, how about—in the documentary when we learn that Tony Bosch had 100 law enforcement clients. We have police officers with a gun and a badge and essentially a license to kill in public service job in a public position of authority who having roid rage out on the streets. How about Congress holds hearings about that? Where are our priorities?

Alfred Spellman: We’re in a society today where kids are given riddelin to compete in competitive chess for us or to perform on the SATs with better concentration. So like I said, I think we used to have a holistic conversation about and define our terms rather than just talking past each other and retreating into tribal corners about what we should consider to be illegal inappropriate. I don’t think we’ve really had that conversation.

Billy Corben: To answer the last part of your question, I don’t care. Should they be in the Hall of Fame or not? I don’t care. That’s my short answer.

Alfred Spellman: I would answer the question about the Hall of Fame that you have spitballers, you have batcorkcers, you have certainly have people with moral turpitude—Ty Cobb is in the Hall. Who we include and who we exclude—I think that since the Pete Rose debacle, this whole discussion about Hall of Fame eligibility is really split into two camps. It’s 21st century analytics-driven baseball crowd verses the 20th century old-school baseball crowd and that’s what demonstrates itself in this conversation on PEDs, the Hall of Fame, the pace of play, and about what the game of baseball is going to be in the 21st century. In a lot of ways, it resembles our politics—the split between the people of last century and the people of this century.

I hadn’t thought of that.

Billy Corben: Sports is the original tribalism. And that’s what our politics have turned into. The idea that we don’t get together collectively and determine how best to proceed for the greater good. We’re like—as long as you’re losing, I’m winning. What kind of attitude is that in a United States? That’s antithetical to progress, to making a better life, a better country, and a better world for all of its citizens. But who cares as long as you’re losing? What kind of a spirit is that? How do you accomplish anything that way. But that’s what sports embodies—that level of competition—tribalism.

The post ‘Screwball’ Filmmakers Explain Why They Used Child Actors in Their Hilarious True-Crime Doc [Interview] appeared first on /Film.

from /Film https://ift.tt/2CFNlfM

via IFTTT

Comments

Post a Comment