The ‘Green Book’ Controversy Explained: A Tour of Hollywood’s Long History of Mishandling Black Stories

Green Book, starring Mahershala Ali as musical prodigy Dr. Don Shirley and Viggo Mortensen as bouncer-turned-actor Frank Anthony Vallelonga aka Tony Lip, just won Hollywood’s biggest honor. But there are many moviegoers out there who are less than satisfied with Hollywood’s love affair with the film. While Green Book has received support for being an entertaining look at an interracial friendship in the 1960s, many are also annoyed with the film focusing more on its white protagonist rather than its black one. It is Dr. Shirley, after all, who is taking a trip throughout the South and performing at prejudiced venues.

The public’s ire over Green Book has only intensified now that the film has won three Academy Awards, including Mahershala Ali for Best Supporting Actor, Peter Farrelly, Brian Currie and Nick Vallelonga (Lip’s son) for Best Original Screenplay, and of course, Best Picture. Many are doing their best to separate Ali, an esteemed and beloved actor in his own right, from the mess surrounding Green Book. But it becomes hard to do that when the higher-ups surrounding the film, such as Vallelonga and Farrelly, went out of their way not to even acknowledge Shirley’s life story during their acceptance speeches. Keep in mind that it is because of Shirley’s life that the film even exists.

It was assumed that Green Book, a film that has been called this century’s Driving Miss Daisy, would probably win Best Picture because of its staid and reductive look at race relations. But even with that disappointing fact staring us in the face, I’m sure there are still people wondering why films like these are still getting made. Even though we are in a post-Black Panther and Hidden Figures world, even though the snubbed If Beale Street Could Talk seemed like a shoo-in for multiple Oscar nominations, why are films about race still hindered by Hollywood?

In Green Book’s case in particular, the question morphs into how could this film compound racial problems with a lack of due diligence as far as research is concerned. The film has been mired in so much controversy, especially when it comes to the feelings of Shirley’s living family, who state that much of the film is false. In short, everything revolving around this film can be surmised in one quick question: How did this get made?

Unfortunately, my deep dive into Hollywood’s psyche surrounding race films and how it led to Green Book is a lot less funny than anything SlashFilm’s HDTGM oral historian Blake Harris has had the privilege to unearth. Instead, I’m looking at Hollywood’s obsession with the concepts of blackness and whiteness as constructs to manipulate and bend towards the will of the racial majority.

The first Hollywood race film

It shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone that Hollywood keeps cranking out similar films about race over and over again. As much as Hollywood wants to be seen as a bastion of liberal thought, it’s actually much more regressive in its views on race.

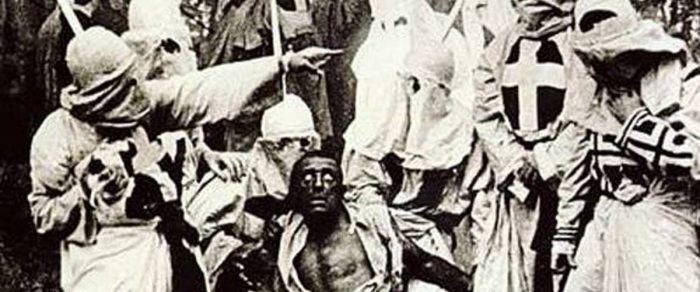

To understand why Hollywood is still battling its regressiveness, it’s important to know how Hollywood became mainstream. The first Hollywood blockbuster is 1915’s Birth of a Nation by D.W. Griffith. The film is considered a technological landmark, utilizing techniques that would be replicated in many of the spectacle films from Hollywood’s Golden Age. But apart from its status as an achievement in cinema, it also stands out as a love letter to the Ku Klux Klan.

In this film, the Klan are positioned as literal white knights, protecting the South from the “scourge” of black people (men in particular). Blackness was seen as an epidemic that needed to be subdued, and the Klan, depicted as noble protectors of whiteness (especially when it came to white womanhood), were just the people to do the deed.

The film’s portrayal of blackness is all types of offensive. There are many white actors in blackface, but there are also actual black actors who played demeaning roles that supported the white supremacist message of the movie. In comparison to this and other issues, the blackface is probably the least of the film’s problems regarding blackness.

Almost every kind of stereotype surrounding blackness is employed, from the happy Mammy figure to the lustful, crazed black man. Black men in particular get it the worst; they are almost zombie-like in the film’s portrayal, with the Klan acting as superheroes taking on the horde. In Birth of a Nation, black people are far from human. They’re not even portrayed as animals. They’re objects at best, and supernatural evil at worst. Birth of a Nation wants to be seen as an apocalyptic film, but instead of the apocalypse being a natural disaster or alien invasion, the apocalypse resides in the alleged sinfulness of black skin.

This film is not only responsible for jumpstarting Hollywood, but it’s also responsible for beginning the industry’s backwards view of race. In many ways, Birth of a Nation simply highlighted society’s already messed-up view of the black American. But the film also magnified those fears, entrenching them in how entertainment would tackle race from then on.

The seeds sown from Birth of a Nation

Ever since Birth of a Nation, Hollywood has internalized some stark stereotypes and tropes about how to relay stories about race. As time has gone on and as movements advanced black Americans, those tropes evolved. But they still functioned from the same concentration of white power in Hollywood.

From Birth of a Nation, Hollywood came up with these tactics for films about race:

- White directors are in charge of telling the narrative of blackness

- White people in power can recreate blackness in their imagination

- Black creatives are left with a lack of access to tell their own stories. Meanwhile, white creatives can be rewarded for their films about racism, whether or not the stories are telling the truth

But how do these rules play out in films? Let’s take a look at each one in depth.

White people in power getting to tell the narrative of blackness

Unfortunately, it’s taken the bloodshed of many black men, women and children for Hollywood, much less the rest of the United States, to recognize that black people were, in fact, people. But even with the recognition that black Americans are owed their inalienable rights, films from the ‘60s all the way to the ‘00s were still largely created from a white point of view. Instead of empowering black filmmakers to tell their stories to a mainstream audience, white directors have been rewarded by making films about race that still center white feelings.

For instance, recent films like 2009’s The Blind Side, starring Sandra Bullock and Quinton Aaron, manipulated the true story of Michael Oher, a man who was taken in by a white family as teenager and went onto become an NFL superstar, into a white savior film. Bullock’s character, Leigh Anne Tuohy, is portrayed as a woman who bravely goes beyond the colorlines to protect a black child from the wrong side of the tracks. It’s positioned that it’s her love and fortitude, not his talent, that lands him with a prime position in college football, his first rung in the ladder towards NFL stardom. We are invested more on Leigh Anne’s humanity as a caring mother who is also a part of a white elite circle of Southern families than we are in Michael’s humanity as a kid who has a broken family impacted by racial and social injustices. Even worse, the humanity of his mother (Adriane Lenox), a drug addict, is denied, despite the fact that her path toward drug use is partially due to racially-biased systems that proliferate drugs in some black neighborhoods.

The Help, another recent film, is based on the 2009 book by Kathryn Stockett, who wrote in her author’s notes that she based her book, essentially, around fan-fiction about her life. Raised in Mississippi, Stockett uses much of her life and her relationship to her family’s maid Demetrie to inform her curiosity about what Demetrie would have said about her own life.

“I’m pretty sure I can say that no one in my family ever asked Demetrie what it felt like to be black in Mississippi, working for our white family. It never occurred to us to ask. It was everyday life. It wasn’t something people felt compelled to examine,” she wrote. “I have wished, for many years, that I’d been old enough and thoughtful enough to ask Demetrie that question. She died when I was sixteen. I’ve spent years imagining what her answer would be. And that is why I wrote the book.”

To her credit, Stockett does write that she doesn’t presume to know what it’s like to be a black woman. “I don’t think it is something any white woman on the other end of a black woman’s paycheck could ever truly understand,” she wrote. “But trying to understand is vital to our humanity.” And, if I’m being honest, I found The Help entertaining as a book. But as the years have gone on, I’ve thought more on the story and how it does a disservice to its black characters, even while doing its best to uplift them.

First of all, even though the main characters are supposed to be maids Aibileen and Minny, the only person with any agency to change things is Skeeter, a white college-age girl who represents the author during her youth. Skeeter wants to write a book that makes a change, so she enlists the maids to tell their stories. But even the act of getting the maids onboard is one of white privilege; she doesn’t understand how even speaking up in opposition could endanger the maids’ already perilous lives. Instead, she seeks to know their story so her book can eventually be on the best-seller list. Their stories are supposed to enlighten readers, but they are also used as a tool to further Skeeter’s career.

Optics only get worse in the film version of the The Help, in which the film tries to rectify some of the maids’ lack of agency. There’s one particular scene that doesn’t exist in the book – the final scene when Aibileen (Viola Davis) finally confronts her evil employer Miss Hilly (Bryce Dallas Howard) and quits. But even in this scene, one that’s supposed to be triumphant, there is still whiteness at work.

Tate Taylor, the writer-director of the film (and Stockett’s longtime friend), had the right instinct to give Aibileen a “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore” type of scene. But after she quits, the audience is left with a lot of questions, some of which might have been answered if a black writer or a writer with more awareness of black Southern life were at the helm.

It’s naive to think that Aibileen could just quit her job in Mississippi during a time when there weren’t a ton of opportunities for upward mobility for black southerners. The idea of quitting could be an option for a white maid, because they could easily go into the city to find upstanding work. But what could Aibileen, an uneducated black woman, do? She’d have to go from one menial job as a maid to another, possibly as a janitor, or more likely, a maid for some other white woman.

Let’s not forget that even though Aibileen quit, she still doesn’t have the upper hand. Hilly still does, and she can still ruin Aibileen’s life by spreading the lie around town that Aibileen is disobedient and hard to work with. Who would hire Aibileen then? How would she be able to make a living? The only other option would be to work in Skeeter’s family’s house, and even if she’s working for a “nice” white family, she’s still working for a white family.

The Help also engages in another sin of Hollywood race films; the tropes of the “nice” white person and the “evil” white person. In this case, Skeeter is seen as the character folks who consider themselves progressive non-racists can attach themselves to. She is the fantasy many white people want to view themselves as; the person who, if the opportunity called for it, would rise to the occasion and stand up for oppressed people.

Meanwhile, Hilly is the person white audiences recognize as the worst parts of themselves; the part that will go along with the status quo, the white patriarchal systems that have been in place in this country since its inception, as long as it works out to their advantage. This opportunistic construct of whiteness overlooks the plight and exploitation of others because there are schools of thought in place to separate whiteness from the guilt of perpetuating slavery, subjugation, and abuse.

The white characters of The Help represent the propensity for Hollywood to insert tropes of whiteness. The working theory Hollywood seems to have is that white audiences cannot bear to be told about how knowingly and unknowingly participate in racist social structures. The guilt, it would seem, would be too much for the conscience to handle. Therefore, Hollywood has created tropes of whiteness that both assuage and remove the pain and trauma of guilt from its audience. These tropes can be seen in films throughout Hollywood’s history.

For instance, let’s look at Quentin Tarantino’s 2012 film Django Unchained. The film is supposed to be about Django (Jamie Foxx) and his search for his enslaved wife (Kerry Washington). Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) is supposed to be Django’s mentor/sidekick, meaning he’s supposed to be a supporting character. But instead, Tarantino’s white guilt heavily informs Schultz as a character – he’s uncommonly innocent about American racism and feels more empathy than even Django does about Django’s predicament. Schultz even delivers the decisive blow to sadistic slaveowner Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio), the act Django was supposed to carry out. Also: his name is Dr. King, for goodness’ sake. He’s named after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

While Schultz is a cartoon of a white guilt, Candie and the KKK members in Django are cartoons of racist white people. They are uncommonly evil, disregarding the fact that many racists of the past and today are everyday people, including your neighbors. The film, like many before and after it, wrongly assert that racism is something that only exists in the extreme. Quite the contrary; throughout history, the most racist people have been the ones who were seen as those working for the common good. Scientists, doctors, politicians, next door neighbors, townspeople – anyone from any of these groups could be as racist as any KKK member. Racism exists the best within the grey areas of life; you don’t need to have a white hood to be proud in ignorance.

Annoyingly, even Spike Lee’s recent film, BlacKkKlansman, participates in these tropes. Ron Stallworth (John David Washington) is supposed to be the lead of the film, but he is often overshadowed by Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver). Some of this is because of the nature of the story – Stallworth is tricking the KKK over the phone, but Zimmerman, a white cop, has to show up to the meetings. However, some of it is also because of the audience Lee is trying to pull. BlacKkKlansman may be a film marketed as one telling a black experience, but it is largely a film for the white audience. It’s informing them about the elements of racism, stuff many black people already know about. It coddles the white audience by showing Stallworth’s story through the experiences of Zimmerman, who has to grapple with his own minority status as a Jewish man.

Zimmerman is BlacKkKlansman’s “good” white person trope in contrast to the KKK members in the film, who are mostly portrayed as country, backwoods idiots. They are portrayed as the dregs of society, obvious to anyone who sees them, but when has racism always made itself known in such an aggressive fashion? Again, racism in film is displayed in the extreme, not where it usually lives, which is in the grey areas of life. It’s in this gray area that black people face the most pernicious problems. Dr. King, in fact, said it best in his Letter from Birmingham Jail:

“I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens Councillor or the Ku Klux Klanner but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says, ‘I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direct action’; who paternalistically feels that he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by the myth of time; and who constantly advises the Negro to wait until a ‘more convenient season.'”

Tropes like these are something I expect from Hollywood in general, but they are hardest to swallow from someone like Lee, who has made it his mission to create films that tell multifaceted stories of black life. Seeing Lee devolve to these cartoony methods of storytelling is frustrating.

I’ll end this section with this: Before anyone gets bent out of shape, I’m not saying every white person is bad. But even with me having to write this statement, I’m participating in the same white supremacist system that begs non-white people to soften or ignore their feelings about their lived-in reality. Not every white person is a bad person. Not every white person is a racist. But as a whole, white people benefit from the racist construct of whiteness. Its ill-gotten beneficial power is why whiteness is a construct that remains powerful to this day. Hollywood’s inability or unwillingness to reckon with this power, the same power that helped build Hollywood, unfortunately keeps fueling the fire.

Continue Reading Green Book Controversy >>

The post The ‘Green Book’ Controversy Explained: A Tour of Hollywood’s Long History of Mishandling Black Stories appeared first on /Film.

from /Film https://ift.tt/2GP4s2A

via IFTTT

Comments

Post a Comment